BCH's TAVR Program Featured in Wall Street Journal

- Category: General, Cardiology

- Posted On:

- Written By: Boulder Community Health

News of two large clinical trials that suggest transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) could benefit a wider group of patients with severe aortic stenosis brought attention last week to Boulder Community Health’s Structural Heart program and director Dr. Srinivas Iyengar, who was quoted in a March 16 article in the Wall Street Journal. The New York Times also published a positive article that day, stating that research showed TAVR "proved effective in younger, healthier patients."

News of two large clinical trials that suggest transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) could benefit a wider group of patients with severe aortic stenosis brought attention last week to Boulder Community Health’s Structural Heart program and director Dr. Srinivas Iyengar, who was quoted in a March 16 article in the Wall Street Journal. The New York Times also published a positive article that day, stating that research showed TAVR "proved effective in younger, healthier patients."

To read the full text of the WSJ article, scroll down or click here (subscription required).

To read the full text of the NYT article, click here.

BCH's Boulder Heart is the only program in Boulder County performing TAVR, an innovative, minimally invasive procedure to replace failing aortic valves. Dr. Iyengar leads the most experienced team in Colorado -- with over 1,000 TAVR procedures performed by himself and Dr. Daniel O'Hair

"Boulder Community Health has established itself as leader in the community not only by investing in TAVR technology but also in the skill and experience needed to deliver the leading-edge care that our community deserves," says Jeffrey Reed, executive director of Specialty Services at BCH. "Dr. Iyengar brings hundreds of cases under his belt -- not just TAVR, but also minimally invasive procedures like Watchman, Mitraclip and PFO closures. In addition, with our world-class cardiothoracic surgery team headed by Dr. Daniel O'Hair and Dr. Bryan Mahan, BCH is poised to take cardiology care to the next level and beyond."

Since the FDA first approved TAVR in 2011, it has been reserved mostly for patients whose age or physical condition disqualify them from having open heart surgery. Access to TAVR also has been generally limited to larger hospitals that perform more procedures each year, due to rules and reimbursement policies set by Medicare, the federal health insurance program for the elderly.

In the WSJ article, Dr. Iyengar said about this issue: “I feel the ivory tower mentality of a lot of major medical centers is to say, ‘We would like this procedure done only in our hospital.' That doesn’t serve the patient’s best interest.”

The two new clinical trials bolster the current debate swirling around the standard of care for most patients with failing aortic valves, since the data shows TAVR is just as effective in younger, healthier patients. On average, the study subjects were in their low to mid-seventies, about a decade younger than current patients.

Cardiovascular surgeons know that valves placed by open-heart surgery tend to last 10 to 15 years. How long TAVR valves will last remains to be determined as the patient data grows. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is expected to propose new rules by the end of this month that would govern which doctors and hospitals can offer TAVR.

Call our Structural Heart coordinator to schedule an assessment with Dr. Iyengar: 303-415-8898.

Hear how TAVR changed these BCH patients' lives

Read on for the full text of both articles:

Tens of Thousands of Heart Patients May Not Need Open-Heart Surgery

Replacement of the aortic valve with a minimally invasive procedure called TAVR proved effective in younger, healthier patients.

by Gina Kolata, The New York Times (March 16, 2019)

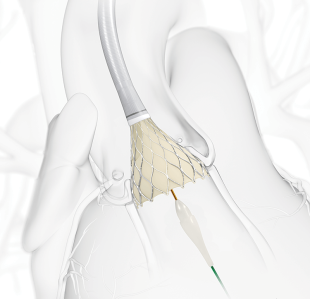

The operation is a daring one: To replace a failing heart valve, cardiologists insert a replacement through a patient’s groin and thread it all the way to the heart, maneuvering it into the site of the old valve.

The procedure, called transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), has been reserved mostly for patients so old and sick they might not survive open-heart surgery. Now, two large clinical trials show that TAVR is just as useful in younger, healthier patients.

It might even be better, offering lower risks of disabling strokes and death, compared to open-heart surgery. Cardiologists say it will likely change the standard of care for most patients with failing aortic valves.

“Is it important? Heck, yes,” said Dr. Robert Lederman, who directs the interventional cardiology research program at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. The findings “were remarkable,” he added.

Dr. Lederman was not involved with the studies and does not consult for the two device companies that sponsored them.

In open-heart surgery, a patient’s ribs are cracked apart and the heart is stopped to insert the new aortic valve.

With TAVR, the only incision is a small hole in the groin where the catheter is inserted. Most patients are sedated, but awake through the procedure, and recovery takes just days, not months, as is often the case following the usual surgery.

The results “shift our thinking from asking who should get TAVR to why should anyone get surgery,” said Dr. Howard Herrmann, director of interventional cardiology at the University of Pennsylvania.

“If I were a patient, I would choose TAVR,” said Dr. Gilbert Tang, a heart surgeon at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, who was not involved in the new research.

The studies are to be published in the New England Journal of Medicine and presented on Sunday at the American College of Cardiology’s annual meeting.

The Food and Drug Administration is expected to approve the procedure for lower-risk patients. As many as 20,000 patients a year would be eligible for TAVR, in addition to the nearly 60,000 intermediate- and high-risk patients who get the operation now.

“This is a clear win for TAVR,” said Dr. Michael J. Mack, a heart surgeon at Baylor Scott and White The Heart Hospital-Plano, in Texas. From now on, “we will be very selective” about who gets open-heart surgery, said Dr. Mack, a principal investigator in one of the trials.

Some healthier patients will still need the traditional surgery — for example, those born with two flaps to the aortic valve instead of the usual three. Having two flaps can lead to early aortic valve failure.

TAVR was not tested in these patients, and the condition occurs more often in younger patients who are low surgical risks.

Aortic valve failure stems from a stiffening of the valve controlling flow from the large vessel in the heart that supplies blood to the rest of the body. Patients often are tired and short of breath.

There is no way to prevent the condition, and no treatment other than replacing the valve. The main risk factor is advancing age.

Although both studies enrolled over 1,000 patients, the trials differed slightly in design, making direct comparisons difficult.

The study led by Dr. Mack and Dr. Martin Leon, an interventional cardiologist at Columbia University in New York, tracked deaths, disabling strokes and hospitalizations at one year following the procedures. The rates were 15 percent with surgery versus 8.5 percent with TAVR.

The rates of deaths and disabling strokes — the factors most important to patients — were 2.9 percent with surgery versus 1 percent with TAVR.

The second study estimated deaths or disabling strokes at two years, finding rates of 6.7 percent with surgery versus 5.3 percent with TAVR.

The trials were sponsored by makers of TAVR valves, Edwards Lifesciences of Irvine, Calif., and Medtronic, headquartered in Dublin. The two companies make slightly different valves.

The Edwards valve is compressed onto a balloon catheter that is pushed through a blood vessel from the groin to the aorta. Once it reaches the aorta, a cardiologist inflates the balloon and expands the valve, which pushes aside the failing valve.

The Medtronic valve is made of nitinol, a metal that shrinks when it is cold and expands when warm. The valve is chilled and put onto a catheter. When it reaches the aorta, the cardiologist pulls back a sheath, freeing the new valve. Warmed by the body, it expands to fill the narrowed opening and remains there.

With traditional surgery, by contrast, a doctor cuts out the old valve and sews in a new one, removing the old valve instead of leaving it in the heart.

Dr. Jeffrey J. Popma, an interventional cardiologist at Beth Israel Deaconess in Boston, led the second trial and is a consultant for both manufacturers. He uses both devices in surgery, and said the important finding is that both [devices] were preferable to surgery.

The studies involved leading surgeons and cardiologists at academic medical centers, many enlisted as consultants. Independent data and safety monitoring committees oversaw the trials, and independent statisticians confirmed the results.

Aortic valve replacements have been performed for decades, and surgeons know the valves placed during surgery last at least 10 to 15 years. It remains to be seen if TAVR valves will fare as well.

The question is especially important for younger patients. The average age of subjects in the current studies was the low to mid 70s, younger by a decade or more than most patients getting TAVR now.

Hospitals offering TAVR will take a financial hit when lower-risk patients start opting for it, Dr. Herrmann said. The TAVR valves cost far more than valves placed surgically, but insurers usually pay equally for either procedure.

“Open-heart surgery, particularly in low-risk patients, is very profitable,” Dr. Herrmann said.

More than half a dozen companies make surgical valves, but only two market TAVR valves. Perhaps with more competition, Dr. Herrmann said, prices for TAVR valves will come down.

At the moment, it will be up to most patients which procedure they choose, Dr. Popma said — TAVR or surgery.

For Robert Pettinato, 79-year-old retiree in Scranton, Pa., there was no question. He had been feeling mild chest pain, and he was finding it difficult to finish a round of golf.

But last year, when his cardiologist told Mr. Pettinato that he needed a new valve, the only way he could get TAVR was to enter a clinical trial. He enrolled in the Edwards trial at the University of Pennsylvania.

He had TAVR in November, stayed in the hospital for 24 hours and went home. A few days later, he went to the football game at Lehigh University against its archrival, Lafayette. (He’s a Lehigh alumnus and never misses that game.)

Shortly afterward, his younger brother Jim, who lives in Florida, had to have aortic valve replacement. He wanted TAVR, but the clinical trials were closed. He had surgery instead.

It took his brother four months to recover enough to play a round of golf, Mr. Pettinato said.

Mr. Pettinato is back to playing golf himself. “I am the luckiest guy in the world,” he said.

Smaller Hospitals Press for Chance to Offer Heart-Valve Procedure

Safety vs. accessibility is at center of debate as Medicare agency is poised to propose new rules

by Peter Loftis, Wall Street Journal (March 16, 2019)

A battle has broken out among doctors, hospitals and medical-device makers over whether an increasingly popular but risky medical procedure for replacing defective heart valves should be offered more widely.

The fight is over which hospitals can get paid by the federal government to perform the procedure, often referred to as TAVR, for transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Currently, bigger hospitals that perform the procedures more frequently are favored under federal reimbursement policies—based on studies linking volume to quality—while smaller hospitals have a tougher time meeting the rules to start or maintain TAVR offerings.

TAVR has transformed treatment of certain heart-disease patients by giving them an alternative to open-heart surgery. Many of these patients are too sick to undergo the risks of open-heart surgery; yet patients undergoing TAVR also are at risk of complications, including stroke.

To ensure safety, TAVR’s use has been effectively limited to bigger hospitals performing at least 20 of the procedures annually. That is because the federal Medicare health insurance program for the elderly, the biggest payer of TAVR bills in the U.S., has limited reimbursement to hospitals that would perform higher volumes of the procedures.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is expected to propose new rules by the end of this month that would govern which doctors and hospitals can offer it. Some doctors, especially those in rural locations where it can be harder to find a hospital performing TAVR, have argued that advancements in the procedure have made it less risky.

The decision could affect revenue of the companies that sell the replacement heart valves. Edwards Lifesciences, the market leader, sold $2.2 billion in the valves world-wide last year, while Medtronic PLC sold about $1.4 billion, according to Jefferies LLC analyst Raj Denhoy.

Medicare’s move also could affect patients. Two new clinical studies published online Saturday by the New England Journal of Medicine suggest TAVR could benefit a wider group of patients, including those deemed healthy enough to withstand open-heart surgery. Researchers are slated to present the results Sunday at the American College of Cardiology’s annual meeting in New Orleans.

One study, funded by Edwards, showed TAVR reduced rates of death, stroke and re-hospitalization versus surgery. A Medtronic study found TAVR was comparable to surgery in rates of death and disabling stroke.

Yet a study published in JAMA Cardiology in 2017 found there was a lower rate of readmission of patients 30 days after TAVR procedures performed at high-volume hospitals, 15.6%, than at lower-volume sites, where rates were 19% to 19.5%. Patients were readmitted for heart complications and infections, among other causes.

TAVR is for patients with a condition called aortic stenosis, caused by a narrowing of the heart valve that can lead to heart failure and death. The procedure consists of threading a catheter through a patient’s artery and then replacing the defective heart valve.

Nearly 200,000 patients in the U.S. have undergone TAVR since it became available in 2011, including more than 50,000 in the first nine months of last year, according to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, which manages the registry of TAVR procedures. The procedures can cost between $50,000 and $60,000 a patient, including hospital admission costs.

Medicare’s reimbursement restriction limited TAVR to about 600 hospitals in the U.S., a little more than half the number that provide heart surgery. That has forced patients in some rural areas to travel far to get the procedure, and led their doctors and hospitals to lobby for expanded use.

Wyoming has no TAVR centers, forcing patients there to drive several hours to hospitals in Colorado or elsewhere, said Dr. Adrian Fluture, a cardiologist in Casper. His practice sends about 30 patients a year out of state because the Wyoming Medical Center in Casper doesn’t have the volume of heart patients to meet the Medicare thresholds.

“Our concern is we’re not offering the right treatment for the Wyoming population,” Dr. Fluture said.

Dr. Fluture and other doctors affiliated with smaller hospitals say CMS should either eliminate volume requirements or make them less restrictive. They say TAVR has become a less complicated procedure since it first came out, and there are existing tools to monitor the safety of procedures, including a national registry of the outcomes of TAVR procedures.

But doctors at larger hospitals and academic medical centers say patient safety calls for restricting TAVR to those who can do the procedure frequently.

“The more you do, the better you get at it,” said Dr. Joseph Bavaria, professor of surgery at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, and co-author of the heart societies’ recommendations. “Some of these complicated things shouldn’t be done at super-small hospitals.” He says Penn’s hospital system performs between 400 and 500 TAVR procedures a year.

“I feel the ivory tower mentality of a lot of major medical centers is to say, ‘We would like this procedure done only in our hospital,’” said Dr. Srinivas Iyengar, who helped start a TAVR program at Boulder Community Health hospital in Boulder, Colo., in 2017. “That doesn’t serve the patient’s best interest.”

The four major organizations representing heart doctors, including the American College of Cardiology, say there is a correlation between volume and quality of TAVR procedures. In a joint proposal to Medicare, the groups recommended raising the volume requirements to hospitals performing at least 50 a year or 100 over two years, up from 20 a year or 40 over two years.

Dr. Allen Baum, president of Cardiology Clinic of San Antonio and supporter of the volume requirements, said in a letter to CMS last year “there are some very powerful lobbying forces that will want to liberalize these criteria because of the financial benefit to their institution. The device industry wants to sell more devices, every small hospital CEO would love to have this done at their hospital.”

Edwards Lifesciences, which initially was selective about which hospitals and doctors could use its valves, now favors dropping the volume requirements and allowing lower-volume hospitals to offer the procedure, saying it has become safer and more routine.

“We’re at a point in time where results have improved dramatically,” Larry Wood, Edwards’ corporate vice president of transcatheter heart valves, said in an interview.

Medtronic favors maintaining current volume requirements until better evidence emerges that they should be adjusted. The company said in a letter to CMS last year the evidence of a correlation between volume and quality is mixed.

Call our Structural Heart coordinator to schedule an assessment with Dr. Iyengar: 303-415-8898